WHEN the world’s best surfers come to Long Beach, N.Y., next month to compete for a record million-dollar purse in the Quiksilver Pro New York, a new event on professional surfing’s world tour, they might be forgiven for using Google Earth to locate the place. Compared with Australia and California and Hawaii, where Quiksilver established its pre-eminence as a beachwear company, New York barely registers on the surfing atlas.

There’s good reason for that: the waves are typically pretty meager here, the winters long and stoke-extinguishing. The competition is scheduled for the first two weeks of September, when the odds of hurricane swells are at their statistical best. Still, as locals will tell you, that’s quite a roll of the dice. If showcasing the underappreciated athleticism of surfing is the goal, why not hold the contest in, say, Fiji or Mexico, where the waves would be far more likely to prove worthy of the surfers?

Perhaps because Quiksilver is coming to town less for great surf than for greater market share.

In the past decade or so, surfing has undergone a worldwide boom in popularity, especially among women and urban professionals in their 20s and 30s. Tom Hanks surfs; Cameron Diaz, too. Surf schools and spa-like resorts, the fastest-growing segment of the surf economy, have sprung up, further altering the character of a sport that was once the realm of working- and middle-class adolescent males and young men whose initiations at local beaches were typically prolonged and humiliating.

Meanwhile, older surfers, who in previous generations would have put aside this childish thing, have kept on surfing or returned to it after a hiatus, in large part because of the renaissance of kinder, gentler designs like the longboard and stand-up paddleboard.

As if suddenly remembering that it’s a coastal city, New York has been swept up in the urban surf craze along with San Francisco and Los Angeles. And why not? New York may not have abundant, grade-A surf but ridable waves are as close as Far Rockaway, Queens, about an hour from Manhattan on the subway.

In New York City, slipping off to ride waves virtually within view of granite Gotham provides a unique, slightly illicit, dreamlike pleasure. Surfing shouldn’t be possible here, and yet it is.

Artists, writers and others in trend-conscious fields are plugged in to New York’s surf scene now, but most of the rest of the city is not, and riding the subway with a board clasped to one’s chest like a dance partner still elicits smiles and queries from otherwise game-faced straphangers. There is something disarming about the sight of a surfboard in New York, where it has a nutty, quixotic quality, like a pair of wings.

When New York City surfers cross paths, they greet one another, exchange notes. Because so many of them are new to surfing, having taken it up in adulthood, they are less like seen-it-all New Yorkers than surfers in pre-“Gidget” California, who would pull over when they passed another car of surfers and introduce themselves. Anyone who has surfed in Santa Cruz or Huntington Beach — chilly, xenophobic “surf cities” — knows how exceptional this urban aloha is.

And if surfing has a soul, it is aloha: welcome, hospitality, generosity without thought of recompense. The word is Hawaiian, of course, and Hawaiians are the ones who gave surfing to the rest of the world. The bitter irony is that the rest of the world returned the favor with a vengeance, and Hawaii’s storied line-ups, flooded by outsiders, are now as famous for being jam-packed and short-tempered as for the waves.

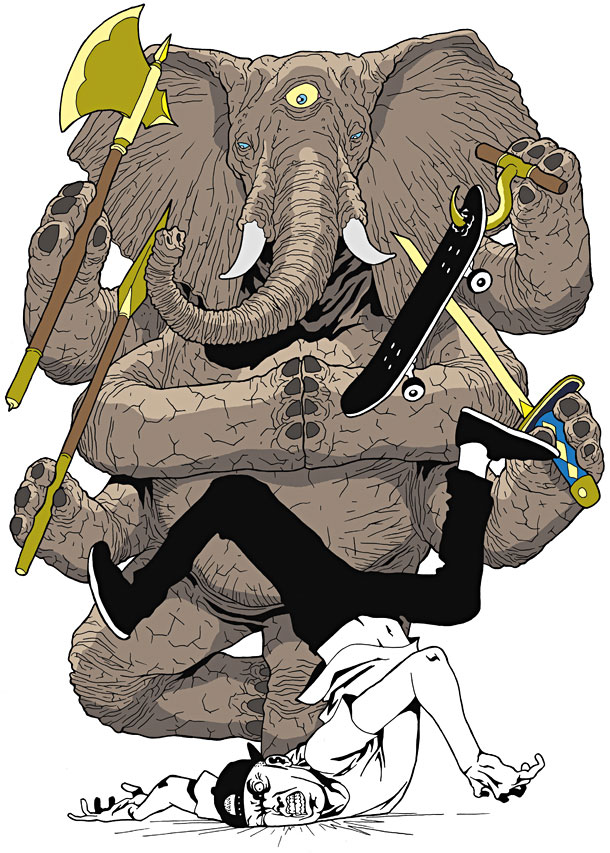

Which is why Quiksilver’s descent on Long Beach is so ominous. Imprinting the Quiksilver brand on New York’s burgeoning surf scene makes perfect sense from a business perspective, but the corporate siren song threatens to sour the mood of surfing in New York, which for the moment remains a bastion of surf spirit. It’s a spirit that companies like Quiksilver claim to value but have in fact helped degrade elsewhere, peddling a vision of surfing’s blithe, blue allure that studiously omits the ugly realities of overcrowding that such marketing abets.

Come what may in the way of waves next month at Long Beach, Quiksilver will do its utmost to lure more people to the sport — and to the cash registers. In an atmosphere of staid, commodified carnival, tents will be emblazoned with sponsor names; top pros will sign posters of themselves riding waves that bear scant resemblance to the nearby surf; and swag will be given away to a milling crowd. There will be a few media types and the odd celebrity, including the 10-time world champion Kelly Slater, and young Balaram Stack, a homegrown star.

Even with such talent on offer, the contest itself may well prove a somewhat dull, obscure affair. Surfing just doesn’t lend itself naturally to formal competition: waves prove too fickle in the best of conditions, and the judging criteria, periodically rewritten though they are, tend to produce relatively safe, conservative performances. The most avid fans of pro surfing are former pro surfers.

And should a good hurricane swell grace the event, a sizable portion of the audience will probably be catching waves of their own rather than spectating along the boardwalk. From Breezy Point to Montauk, the breaks will be stippled with the seal-like forms of surfers celebrating a spontaneous pagan holiday, work and school happily spurned.

It’s not hard to imagine New York’s urban aloha going the way of its Polynesian progenitor, but for the moment a genial, just-folks atmosphere reigns. That’s because it’s still possible to find a bit of ocean to oneself here. And if living in New York proves anything, it’s that it only takes a little — quiet, green, surf — to suffice.

Would that Quiksilver and its confreres learn the same lesson.

Thad Ziolkowski is the author of the memoir “On a Wave.” He directs the writing program at Pratt Institute.

source:

The New York Times

![ZERO6 arte/desordem [art/mess]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiCCGh2aR4viN2YAm0bsdEcBX6xFeyydppbNFcUh59WYKD_IhR9arh9gtZObFkA6KaXowqDPTUEti_KAEEWkGxgOahP9V9Oh4g7s1tYohzcvy_-XGDqE23pfqvBFy48XIOr1jqB-OptmrZO/s1600/cabe%25C3%25A7alho+white+trash.jpg)